In his 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, 28-year-old French poet and cultural firebrand Andre Breton wrote that “the realistic attitude…clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit… It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog’s life.” Breton and his co-conspirators had lived through the Great War — many of them seeing the action of the trenches first-hand — and emerged pissed off at the seeming nonchalance of the world around them. Why were we rebuilding everything to resemble the way it was before? Where were the cries for a social and cultural reckoning? Where, the surrealists wondered, were the true artists? The ones who, you would think, might have a thing or two to say about the way the known moral order of things had flipped on its head? Well, they were on the way, it turns out (obviously), and by “on the way” I mean in many cases they were sitting right there in the room wondering where the true artists were.

I first came across Breton’s manifesto more than 15 years ago and (along with Antonin Artaud’s “No More Masterpieces”) it immediately became one of the core texts of my life. I found it to be an exhilarating piece of writing as I entered into my twenties and worked to make sense of what it meant to make an independent life of purpose and integrity, and as I’ve aged closer to my forties the furious credo of surrealism has only become louder and more urgent. “The mind of the dreaming man is fully satisfied with whatever happens to it,” Breton writes. “The agonizing question of possibility does not arise… Let yourself be led. Events will not tolerate deferment. You have no name. Everything is inestimably easy.” He’s writing about dreams here in a very literal sense, of course (or at least as literal as dreams can be), but those final two sentences have come to have a more profound effect on me than just about anything else I’ve read in my life. This is how I would like to live; this is what I like to remind myself of. This world is a dream. Possibility is agonizing. I will, instead, let myself be led. I have no name. Everything is inestimably easy.

There’s a common misconception, I think, that “surreal” art is simply “trippy” for the sake of the trip, that it’s primarily made and appreciated by drug users, basic art snobs, and black light poster enthusiasts. But I’ve always taken my cues on surrealism from Breton & co.’s insistence on dreams, not as Freud worked to understand them — as signposts to the subconscious — but as examples of what our waking world could aspire to: formless, without a nagging narrative cleanness, and unbidden by self-imposed gutter bumpers. This is why, I think, the work of the Wachowskis and Hayao Miyazaki — by all accounts my favorite filmmakers — moves me so profoundly and so consistently. Even with a story, even within its rules (and sometimes there are many), there is still space for the unexplainable and unexpected, still reverence paid to the beautiful and daring sleeping mind.

If you know about Suzan Pitt, the great belated painter and animator, you likely know Asparagus, her boldly and joyfully surrealist 18-minute short from 1979. Asparagus is the kind of film you understand right away is unlike anything else you’ve ever seen, not because of the scene where a woman shits out asparagus stalks, but because that’s the very first scene. “All of my films come from an internal place — a mental place — inside of me, more than they come from the outside world,” Pitts says in Persistence of Vision, the 2006 short doc her son and daughter-in-law made about her life and work. She says she wanted Asparagus to feel “as though you were daydreaming the images,” that she wanted it to feel like the images drifted between one another in the same way a dreaming mind conjures them up. You can feel this impulse in the film right from the start, giving its depiction of a silent, faceless woman gathering bizarre objects together in an act of equally freeing and confusing creative processes a strangely relatable propulsion. This is what it feels like to make something from nothing, you think as you watch an armchair and lamp burst into colorful sparks. How did you know?

Pitt has said that Asparagus is about “interior imagining, interior searching, interior sense-making,” and that she built it intentionally for the audience to be able to enter in at any point and confront “the same complex of ideas,” as if it were a moving circle. The magic of the thing is that all of that is apparent in the film itself — Asparagus is shapeless and shifting, but it never alienates. It simply invites you to be fully satisfied with whatever happens; it asks you to come in, sit a spell, and dream.

I stumbled across Suzan Pitt’s animated shorts the other day while combing through Mubi in an attempt to ensure I get my 3-month free trial’s worth before it finally ends next week. I had heard about Asparagus (her best known work initially and primarily because theaters screened it in front of showings of Eraserhead at the turn of the ‘80s), and when I saw it was housed on Mubi with the rest of her brief oeuvre, I started from the top and burrowed in.

Her first film, Crocus, is slim at a dialogue-free six-and-a-half minutes, but prescient in its depiction of the themes Pitt would continue to explore throughout her career in animation: waking dreams, sexual agency, and the feminist lens. In its DNA you can see the artist working through the beginnings of a style to call her own, the 8mm grain twitching as nude cut-outs float gauzily over hand-drawn cels, and a climax where disparate cartoonish images — a cucumber, a pink Christmas tree, a spinning head of cabbage — float through an open window. It’s nothing short of a funny and surprising glimpse into a very focused mind.

Pitt’s next film, Jefferson Circus Songs, is likely her least well known and least discussed. She made it in a high school gymnasium in the summer of 1973 with a gaggle of schoolchildren and a team of Minnesotan artists, expanding her palette to include live-action stop-motion while continuing to hone her particular brand of friendly nightmarish hand-painted characters. The film is a true fever dream, more of a skill showcase than anything else, but I find a kernel of genius in the way it employs children. Pitt has often said that artists are people who have retained the play from childhood that is knocked from us as we age, and it’s a lot of fun to see this purity displayed writ large on screen — she’s dressed the kids up as exaggerated clowns and living surrealist sculptures, and you can tell how much fun they’re having playing in that space for her, and more importantly for themselves.

From here Pitt makes Asparagus, which took five years, and it isn’t until 1995, after 15 years of painting and teaching at Harvard and Cal Arts, that she releases her next short, Joy Street, about a woman in a deep depression who is rescued by a ceramic mouse ashtray that comes to life and leads her into a bright and lively jungle. It’s funny now to watch Joy Street immediately after watching Asparagus and know that there is a decade and a half between them. You can see so clearly in its fluid animation and more detailed character design that the technology has changed and Pitt’s own voice has changed as well. It’s also obviously Pitt’s most personal project, in the way pretty much every great project about depression (Kid A, Melancholia, It’s Such a Beautiful Day) is so transparently made from inside of it. In this case, the artist came out the other side by escaping to Mexico and Guatemala, where she painted much of Joy Street on the edge of lush, overwhelming rainforests. I find the film to be deeply hopeful in the end, and very moving in the way it uses music, colors, and dream logic to reach honesty.

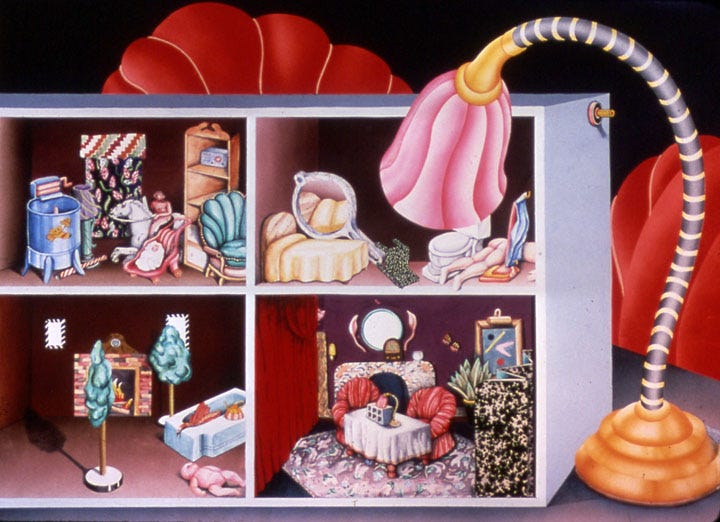

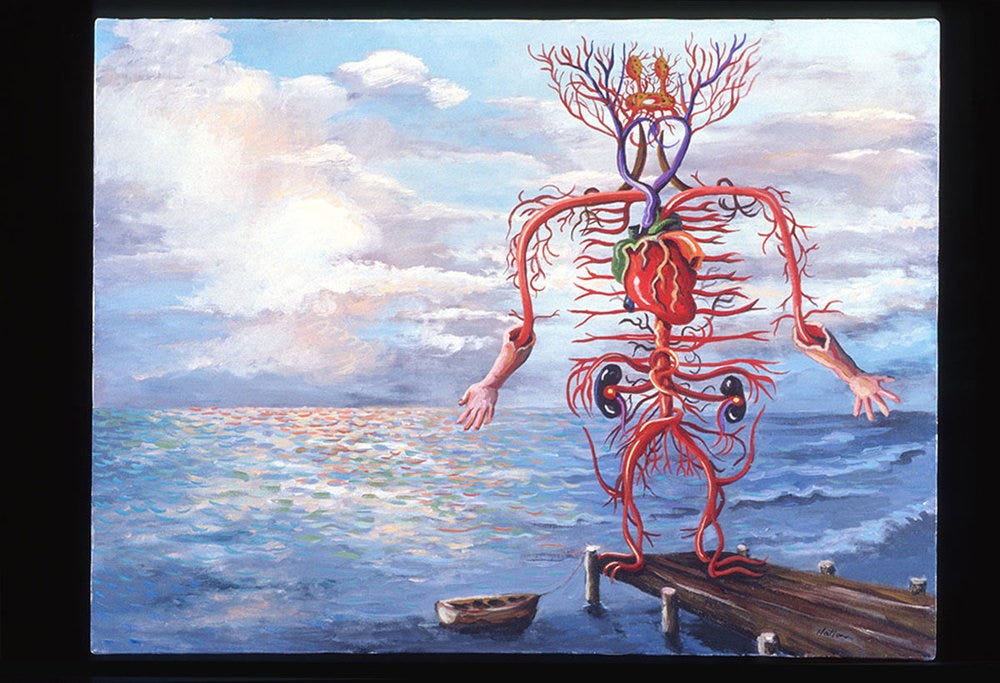

In the 2000s, Suzan Pitt made El Doctor, about a cynical Mexican doctor who has a heart attack and in his dying moments dreams up a series of medical miracles that help to bring him peace; Visitation, a stunning 7-minute non-narrative nightmare that was “summoned from the film maker's imagining of a mythical eternity which is beautiful but fraught with pain, exposed by the ether voices and figures which inhabit the eternal ballet beneath our consciousness” (awesome); and her final film, Pinball, composed of epileptic shots of several brightly colored abstract paintings scored by George Antheil’s essential 1952 revision of “Ballet Mecanique” (in my opinion, this is her least successful piece). El Doctor is the most ambitious of these, and the most straightforward of all of her films, and much of the aforementioned Persistence of Vision focuses on its creation (including animating sand (!!) for one scene and painting neon directly onto the celluloid for another). Like Pitt’s entire oeuvre — including her paintings, which evolved over the decades from Crumb-like pop culture collages, to depicting surreal clashes between the natural world and the one of dreams, to eventually coming all the way around to a more formal abstraction — her final films are endlessly surprising and incredibly moving in the same way our own imaginations can surprise and move us.

In 1979, when Asparagus was blowing up in its own tiny way, Suzan Pitt gave an interview to John Canemaker at Funnyworld where they discussed the childlike impulse to play, and in playing to bring the dreaming world to our own. “It's so hard to talk about,” Pitt says. “As an adult, it sounds neurotic to say I'm afraid of real life. But as children we take objects and move them around. Inanimate objects seem to have life. Do you remember playing with your fingers? I did it really a lot. Played with my doll house, toys out in the back yard. Making arrangements, making them talk and do things. Then as you grow up you're expected to take all that and make it disappear in the closet. What happens to that impulse, that drive to transfer what you see around you into playthings?” It’s a question I think about a lot, as I’m sure anyone who yearns to create does. “So strong is the belief in life, in what is most fragile in life – real life, I mean – that in the end this belief is lost,” Breton wrote 100 years ago in his Manifesto of Surrealism. “Man, that inveterate dreamer, daily more discontent with his destiny, has trouble assessing the objects he has been led to use…for he has agreed to work.”

Watching the surreal worlds of Suzan Pitt come to life, it’s hard not to return to all of this: a belief in life, a doll house, the fingers on our hands. For a few minutes with Pitt’s films — colors begetting colors, dreams becoming image — everything is inestimably easy.

All of the films mentioned above are currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and Mubi. Most are also available in good HD transfers on YouTube.

Movies I watched this week: El Doctor, Visitation, Pinball, and Suzan Pitt: Persistence of Vision || Mangrove and Alex Wheatle (squealed like a little mouse when I saw Small Axe went up on Kanopy) || Frankenhooker (leaving Criterion Channel today! Watch immediately!!) || Night of the Comet (a movie that sets up “Valley Girls fight post-apocalyptic zombie hordes with Uzis,” then just kind of decides not to do that… still good though) || The Color Purple (woefully unsuccessful) || Battleship Potemkin (showed in Film Studies; student freaked at the Odessa Steps sequence, proving that Eisenstein’s still got the juice) || Passages (spent this second watch locked in on how many shots of Tomas show us his back — great movie that reminds me of Girls)

No Montage next week, for I will be in New York sprinting from grad school visits to job hunting to museums and meals with friends. Hoping to catch some of the Suzan Pitt they have at MoMA. See y’all in a couple weeks.

I just watched Jefferson Circus Songs and was sort of confused about the whole thing but I came across this article on Google, trying to find more about JCS and Suzan Pitt. Thank you for this great article!